Stand Columbia: Annotated

For anyone in the Columbia University community who’s just woken up from a coma, a few weeks ago the President of the United States announced that he was freezing $400 million in grants to Columbia “due to the school’s continued inaction in the face of persistent harassment of Jewish students.” Soon afterwards, his administration issued a letter to the school that “outlines immediate next steps that we regard as a precondition for formal negotiations regarding Columbia University’s continued financial relationship with the United States government.” Among other things, the letter demands that Columbia ban masks on campus, adopt a definition of “antisemitism,” place the Middle East, South Asian, and African Studies Department (MESAAS) “under academic receivership for a minimum of five years,” and provide a plan for “comprehensive admissions reform.” The administration’s actions, which have been described as a “mob boss” sending a “ransom note,” are an unprecedented attack by the federal government on America’s intellectual institutions and free speech.

Columbia’s then interim President, Dr. Katrina Armstrong, and the Board of Trustees quickly agreed to most of the administration’s demands, including appointing a senior vice provost to oversee MESAAS, shocking many professors, students, alumni, and observers. And President Trump appears to have used his victory over Columbia as a template to go after Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, Brown, Cornell, Princeton, and Northwestern.

Shortly after the agreement was announced, the Stand Columbia Society published a lengthy newsletter arguing that the school essentially had no choice but to cave to Trump’s demands and that its $15 billion endowment cannot be used to make up for the loss of federal funding. What is Stand Columbia? Its mission and politics are vague, but they describe themselves as a group of faculty, staff, students, alumni, and friends of Columbia “who are dedicated to a single purpose: ‘advocating for Columbia University’s core mission of excellence in teaching, learning, research, and patient care and restoring it to its rightful pre-eminence in American—and global—higher education.’” They also claim to be non-partisan:

We are politically neutral and focused solely on academic excellence and improving our campus climate and culture. These endeavors are not about ‘left’ or ‘right’ but about truth and freedom. Our pursuit isn’t driven by political trendiness or cultural opportunism.

As a graduate of both Columbia College (’94) and Columbia Law School (’00), and as the parent of a current student (‘25), I have of course been closely following these events, as well as the student protests that preceded and to some extent precipitated them. And it is because of my experience with Logic and Rhetoric (aka University Writing) and CLS classes that I can’t resist the urge to pick apart Stand Columbia’s newsletter. And I believe I have standing to do so (pun intended). My commentary on the newsletter, which I found to be filled with bad faith arguments and logical fallacies, is below.

We’re in the second paragraph and the authors have already resorted to a textbook strawman: a pointless and easily defeated argument that was set up just to be knocked down. What does the federal government’s total budget have to do with the issues at hand and Columbia’s endowment? Yes, the federal government’s outlays dwarf Columbia’s, but we all knew that already, so mentioning it adds nothing to the conversation.

More importantly, if no individual or organization “can outspend or outmaneuver the federal government,” does that mean no one should try? I don’t think this country was founded on the notion that the people are powerless and shouldn’t challenge the authority of the hegemon. If Columbia believes this, it should change the name back to King’s College.

I’m pretty sure my CC and CLS professors would frown on arguments that substitute snide comments like “chest-beating chickenhawks” for actual, substantive argument. This is nothing more than an ad hominem, a personal attack against the people making the argument instead of the argument itself. Moreover, the slightly hysterical tone of this paragraph calls to mind Queen Gertrude’s line “the lady doth protest too much, methinks.” (Thank you, Professor Tayler.)

In addition to the mean-spirited ad hominem attack on Dr. Roth and his supposed lack of courage, it’s not clear why the relative sizes of the schools and their federal research grants are relevant apart from a desire for Stand Columbia to beat its chest about the size of its...funding. The issue here is whether the loss of federal funding would be an existential threat to the schools. It’s true that Columbia gets a lot more money from the government, but it’s also a much, much larger school. Now, does the loss of federal funding pose a greater threat to Columbia than Wesleyan? Almost certainly. But the writer undermines this basic point with hyperbole and personal attacks.

Now we’re getting into really bizarre territory. I assume the author brought up Burr and Hamilton to inject a note of humor and add a cute rhetorical flourish, but it doesn’t come across that way. Instead, it reads more like an institutional ad hominem, telling us not to take Dr. Eisgruber’s arguments seriously because of a supposed beef between the schools that absolutely no one alive cares about.

Again, a silly strawman. No one believes or is claiming this.

Finally, they’ve put some meat on the bones and made an actual argument. The New York laws they reference are NPCL §555(a), which allows an institution to modify or release a restriction with the donor’s consent, and § 555(b), which states that:

A court, upon application of an institution, may modify a restriction contained in a gift instrument regarding the management or investment of an institutional fund if the restriction has become impracticable or wasteful, if it impairs the management or investment of the fund, or if, because of circumstances not anticipated by the donor, a modification of a restriction will further the purposes of the fund. The institution shall notify the donor, if available, and the attorney general of the application, and the attorney general and such donor must be given an opportunity to be heard. To the extent practicable, any modification must be made in accordance with the donor's probable intention.

It’s true that these “restrictions are serious,” but we have no idea if any of the donors would be willing to allow Columbia to use their donations to make up for funding shortfalls. Has the school asked?

The newsletter seems to dismiss the second option out of hand, but New York gave institutions the ability to ask a court to modify a restriction for a reason, and the authors of the newsletter provide no explanation why the school shouldn’t at least try to use this provision. The President of the United States threatening to cut funding in an unprecedented and unconstitutional attack on academic freedom seems to fit the definition of “circumstances not anticipated by the donor” pretty well. There’s very little caselaw in New York applying and interpreting this statute as far as I can tell, but I think Columbia would have a strong argument to modify some of the restrictions on its endowment in light of Trump’s attacks.

Here, the authors make no effort to engage with the university policies and law they cite or explain why using unrestricted funds to fight Trump wouldn’t be a prudent use of the endowment.

Regardless, it’s not clear why Columbia would have to use the endowment’s principal to fight Trump. According to the school’s FY2024 financial statement, the school received $539 million in investment income that is not subject to donor restrictions. And even if Columbia needed to use the capital, the very “decapitalization” page the authors link to gives the school wide latitude in using the capital of unrestricted funds: “[U]nder NY law, if the donor has not provided specific instructions either in a gift instrument or certain other writing, the University may appropriate so much of an endowment fund as is prudent for the uses, benefits, purpose and duration of the fund.”

A lawyer would object to the final point about the 2008 financial crisis and COVID on the grounds that it assumes facts not in evidence, while a teacher of logic and rhetoric would call this begging the question. Either way, the authors take it as a given that the school faced similar existential threats in 2008 and 2020, but haven’t presented any evidence to back up that claim. Those were difficult times, but I don’t remember Columbia or any other major universities claiming that they might not be able to survive, so I don’t think the comparison holds any water.

I would hardly call this meaningless. The professors have said publicly that they would be willing to make sacrifices to help the university fight back; that has to count for something. It’s certainly braver than anything Stand Columbia is doing or proposing, i.e., nothing.

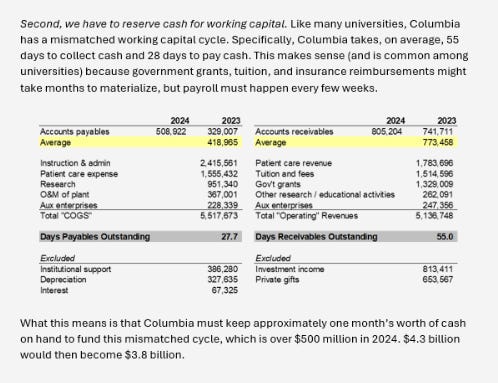

A 10% loss in value would certainly be a blow to the school, but it’s hardly determinative. $4.3 billion in cash is still a significant pot of money, and probably enough to make up for the shortfall in federal funding. Trump threatened to cancel $400 million federal grants, but to my knowledge hasn’t provided any details on the specific projects or the time frame. If $400 million is spread out over a five year period, Columbia needs to make up $80 million per year, an amount easily covered by the unrestricted endowment funds. Even if the $400 million is an annual shortfall, $4.3 billion would take care of the shortfall for almost 11 years.

It’s not clear why the $500 million in working capital would need to come out of the endowment specifically since the school is already keeping the necessary cash on hand. In other words, it appears that the authors are double counting the $500 million by including it in the overall Columbia budget and as working capital.

The authors are moving the goalposts: What was $400 million in cuts over an indefinite period of time now turns into $2 billion per year. To be fair, it’s certainly possible that if Columbia decided to fight, Trump would try to cut all $2 billion in annual funding, but that would put him on even shakier legal ground than he is currently. But even if we assume the worst case scenario, two years is a lot of time to fight Trump in court and lobby donors and Congress for help.

Moreover, the authors never address what should be an obvious solution: using the $15 billion endowment to get a line of credit to make up for any shortfalls in federal funding. Debt isn’t ideal, but it’s an option that should be considered.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to argue with this point. The administration has broad authority to cancel student visas, and could inflict a lot of damage on Columbia by doing so. But cancelling thousands of visas just to punish the school would be a significant escalation in this dispute and risks international blowback and retaliation.

The tone of this paragraph suggests legal victory is unlikely, but the authors offer no reason why we should accept that as a given. The administration has already lost a number of cases challenging its attempts to strongarm and blackmail institutions into doing its bidding, and Columbia has strong legal arguments to fight back against the administration’s attempted extortion.

Are faculty more or less likely to leave now that the school has decided to sacrifice academic freedom by coming to terms with Trump? Some faculty are undoubtedly relieved and happy to have their funding restored, but many others–upset that the school gave in so quickly to a bully and a tyrant–are eager to leave. I don’t know how many fall in the former category or the latter, but neither do the authors. The point is that there’s risk to Columbia either way, which to me tilts the scales in favor of the moral choice. (Moreover, the authors assert that faculty departed because of the 1968 crisis, but I’m not aware of any such examples and the authors provide no evidence to support this claim.)

Once again, a claim that’s not backed by any argument or facts. If the Democrats take the House and Senate in 2026, only a year and a half away, they could impeach Trump and/or block many of his actions.

Another strawman. We don’t need to believe that “fighting Trump” will triple the donations because we don’t need donations to cover the entire $2 billion loss. As noted, the $2 billion total is itself a result of the authors moving the goalposts; the current loss is $400 million over an indeterminate number of years. It’s certainly possible that Columbia alumni could make a significant dent in that number if the school made a special appeal. We simply don’t know at this point. (It’s also possible that alumni donations will decrease in the wake of the school’s capitulation.)

Talk about burying the lede. We’re almost at the end of a very long newsletter when the authors admit that they actually support Trump’s demands. They’re entitled to their opinion, but I think they should have made that position clear up front instead of pretending that this is simply about money.

And, for the record, this is not just about “the right of students to take over University buildings.” The authors conveniently forget that Trump also asked for oversight of the MESAAS department, a shocking demand for thought control that would not be out of place in China during the Cultural Revolution or Afghanistan under the Taliban. I think the protestors are obnoxious, misguided, and, in many cases, antisemitic, but it’s not the federal government’s place to tell the school how to discipline its students or run its campus. And it is most certainly not the President’s place to tell a university what to teach. No other President has attempted to do this for good reason – it’s unlawful and profoundly immoral.

The sarcastic “if they even have them” aside implies that the authors view the non-STEM humanities professors at the school as less important because they don’t generate revenue through federal grants. (And, let’s be honest, because they’re more likely to support the student protestors.) I understand and appreciate the importance of the STEM researchers at the school, but it’s bizarre to discount the importance of the humanities at Columbia, the home of the Core, of all places.

First, the overall angry tone of this piece, including the above reference to “armchair warriors,” suggests that the authors are not confident in their arguments and know that they’re on thin ice intellectually and morally. Second, I agree that Columbia is important, but that belief leads me to the opposite conclusion. Columbia University is too important to the United States and the rest of the world to sacrifice its intellectual independence and integrity by kneeling at the feet of an autocrat.

* * *

Columbia could have stuck to its principles and fought back against Trump through a combination of debt, spending down part of the endowment, and tightening its belt. So I must conclude that Columbia, or, more accurately, the Trustees, accepted Trump’s terms because they wanted to, not because they had to. And for someone who has a deep personal connection to the school and its history, that is a bitter pill to swallow.

As I was writing this, Harvard’s President, Alan Garber, announced in a letter that the school will not accept Trump’s proposed agreement and that “[t]he University will not surrender its independence or relinquish its constitutional rights.” President Garber went on to state that:

The administration’s prescription goes beyond the power of the federal government. It violates Harvard’s First Amendment rights and exceeds the statutory limits of the government’s authority under Title VI. And it threatens our values as a private institution devoted to the pursuit, production, and dissemination of knowledge. No government—regardless of which party is in power—should dictate what private universities can teach, whom they can admit and hire, and which areas of study and inquiry they can pursue.

I must confess that Harvard’s announcement was bittersweet. I’m thrilled that a school is fighting back and refusing to bow down to Trump. But I wish it had been Columbia.

Every Columbia student and alum is familiar with Columbia’s fight song, “Roar, Lion, Roar.” It’s a little cheesy, and as Columbia students we’re required to roll our eyes a little at it and other expressions of school spirit. But while I’m loath to admit it, even a diehard cynic like me can get a little misty-eyed hearing the song and thinking about what the institution means to me.

Roar, Lion, Roar!

And wake the echoes of the Hudson Valley!

Fight on to vict'ry evermore,

While the sons of Knickerbocker rally 'round

Columbia! Columbia!

Shouting her name forever

Roar, Lion, Roar!

For Alma Mater on the Hudson Shore!

Caving to the demands of a petty, immoral, idiotic despot who doesn’t care about scientific research, the humanities, the rule of law, or any of the other values that make Columbia and its legacy great is not fighting for alma mater. Quite the opposite. Making a deal with the devil for some temporary relief does not honor the legacy of Alexander Hamilton, Paul Robeson, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Barack Obama, Shirley Chisholm, Lionel Trilling, Jack Greenberg, Harlan Fiske Stone, or any of Columbia’s countless other distinguished alumni. Yes, there are significant risks in pushing back against Trump and refusing to make a deal. But my Columbia education taught me to do just that. Stand up for what I believe in. Stand up to tyrants and bullies. And stand up for intellectual freedom.